- Available now

- Newly Added Audiobooks

- New kids additions

- New teen additions

- Most popular

- Audiobooks for Finding Peace & Happiness

- Try something different

- See all

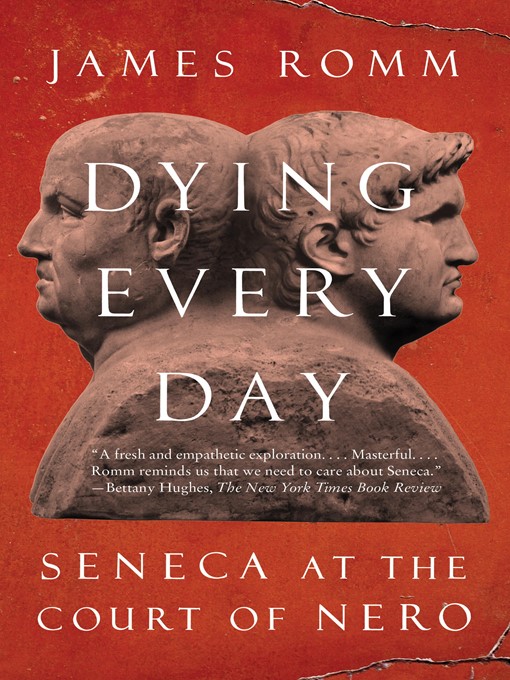

At the center, the tumultuous life of Seneca, ancient Rome’s preeminent writer and philosopher, beginning with banishment in his fifties and subsequent appointment as tutor to twelve-year-old Nero, future emperor of Rome. Controlling them both, Nero’s mother, Julia Agrippina the Younger, Roman empress, great-granddaughter of the Emperor Augustus, sister of the Emperor Caligula, niece and fourth wife of Emperor Claudius.

James Romm seamlessly weaves together the life and written words, the moral struggles, political intrigue, and bloody vengeance that enmeshed Seneca the Younger in the twisted imperial family and the perverse, paranoid regime of Emperor Nero, despot and madman.

Romm writes that Seneca watched over Nero as teacher, moral guide, and surrogate father, and, at seventeen, when Nero abruptly ascended to become emperor of Rome, Seneca, a man never avid for political power became, with Nero, the ruler of the Roman Empire. We see how Seneca was able to control his young student, how, under Seneca’s influence, Nero ruled with intelligence and moderation, banned capital punishment, reduced taxes, gave slaves the right to file complaints against their owners, pardoned prisoners arrested for sedition. But with time, as Nero grew vain and disillusioned, Seneca was unable to hold sway over the emperor, and between Nero’s mother, Agrippina—thought to have poisoned her second husband, and her third, who was her uncle (Claudius), and rumored to have entered into an incestuous relationship with her son—and Nero’s father, described by Suetonius as a murderer and cheat charged with treason, adultery, and incest, how long could the young Nero have been contained?

Dying Every Day is a portrait of Seneca’s moral struggle in the midst of madness and excess. In his treatises, Seneca preached a rigorous ethical creed, exalting heroes who defied danger to do what was right or embrace a noble death. As Nero’s adviser, Seneca was presented with a more complex set of choices, as the only man capable of summoning the better aspect of Nero’s nature, yet, remaining at Nero’s side and colluding in the evil regime he created.

Dying Every Day is the first book to tell the compelling and nightmarish story of the philosopher-poet who was almost a king, tied to a tyrant—as Seneca, the paragon of reason, watched his student spiral into madness and whose descent saw five family murders, the Fire of Rome, and a savage purge that destroyed the supreme minds of the Senate’s golden age.

-

Creators

-

Publisher

-

Release date

March 11, 2014 -

Formats

-

OverDrive Read

- ISBN: 9780385351720

-

EPUB ebook

- ISBN: 9780385351720

- File size: 16468 KB

-

-

Languages

- English

-

Reviews

-

Kirkus

January 1, 2014

There were many sides to the great Roman philosopher and writer Seneca. Romm (Classics/Bard Coll.; Ghost on the Throne: The Death of Alexander the Great and the War for Crown and Empire, 2011) explores his contrasting, even conflicting, skills in surviving at the dangerous court of Nero. Seneca was a sage who preached a simple, studious life while amassing wealth and power in Nero's court. Romm, who teaches Greek literature and language, combed Seneca's profuse writings in an attempt to identify the true man. Was he a moral philosopher of the Stoic school or a greedy businessman and corrupt power monger? Are his tracts really political treatises, or were they propaganda, expounding his ideals or improving his image? The source material is vast, and the author seems to have explored it all: the Annals of Tacitus, the anonymous play Octavia and Cassius Dio's Roman History, along with writings by Suetonius, Plutarch and many others. Julia Agrippina the Younger recalled Seneca from Corsican exile to act as a tutor to her son, Nero, who she intended would succeed Emperor Claudius. Working with Nero must have been exceedingly unpleasant. He was a petulant, spoiled megalomaniacal brat likely responsible for Claudius' death and undoubtedly responsible for his brother's and mother's deaths and countless more. Seneca certainly failed to instill Stoic values in Nero, and he had little luck controlling him. He was the speechwriter, spin doctor, and image maker and became a wealthy landowner thanks to Nero's gifts. "As he himself implied in one of his several apologias," writes the author, "he was not equal to the best, but better than the bad." The task of determining Seneca's true nature is daunting, but the wide body of information available to Romm enables him to give us tantalizing but ambiguous clues to the man's mind. Like any good philosopher, he only shows us the questions and leaves readers to figure out the answers.COPYRIGHT(2014) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

-

Booklist

February 1, 2014

Was Roman philosopher Seneca the Younger an exemplar of Stoic virtue who, pulled into politics in the service of Emperor Nero, did his best to modulate the young despot's cruelty? Or was he a shrewd manipulator whose ethical treatises were just a cynical attempt to restore a reputation sullied by his complicity in Nero's cruel and decadent court? Tacitus, who wrote a lot about Seneca, seems to have had trouble making up his mind. Romm suggests that we might bring together these conflicting portraits by understanding Seneca as a serious thinker who suffered from passivity and obsequiousness, and had the misfortune to live at a time when intellectual activity had become particularly dangerous. Seneca's elegant humanistic vision (which would influence, among other things, Roman Catholic church doctrine), therefore, was not fraudulent, but aspirational, and somewhat tragic: ideals articulated by a flawed man who was all too aware of his inability to live up to them. Vividly describing the intensity of political life in the Nero years, and paying particular attention to the Roman fascination with suicide, Romm's narrative is gripping, erudite, and occasionally quite grim.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2014, American Library Association.)

-

Formats

- OverDrive Read

- EPUB ebook

subjects

Languages

- English

Loading

Why is availability limited?

×Availability can change throughout the month based on the library's budget. You can still place a hold on the title, and your hold will be automatically filled as soon as the title is available again.

The Kindle Book format for this title is not supported on:

×Read-along ebook

×The OverDrive Read format of this ebook has professional narration that plays while you read in your browser. Learn more here.